By Alderi Souza de Matos

Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to present a panoramic view of the history of Protestantism in Brazil. It begins with the first Protestant manifestations in the colonial period, continues with the definitive implantation of the movement during the empire (in both historical modalities: immigration and mission Protestantism), and arrives in republican Brazil, with the emergence of matrix Protestantism Brazilian.

The political-religious context (1500-1822)

Portugal emerged as an independent nation of Spain during the Reconquista (1139-1249), that is, the struggle against the Muslims who had conquered much of the Iberian Peninsula several centuries before. His first king was D. Afonso Henriques. The new country had strong links with England, with which it would later sign the Treaty of Windsor in 1386. The apogee of Portugal’s history was the period of great navigations and great discoveries, with the consequent formation of the Portuguese colonial empire in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

At the end of the Middle Ages, the strong integration between the church and the state in the Iberian Peninsula gave rise to the phenomenon known as “patronage” or royal patronage. By the standard, the Church of Rome gave a civil ruler a certain degree of control over a national church in appreciation for its Christian zeal and as an incentive for future actions in favor of the church. Between 1455 and 1515, four popes granted patronage rights to the Portuguese kings, who were thus rewarded for their efforts to defeat the Moors, discover new lands, and bring other peoples to Christianity.

Therefore, the discovery and colonization of Brazil was a joint venture of the Portuguese State and the Catholic Church, in which the crown played the predominant role. The state provided ships, funded expenses, built churches, and paid the clergy, but also had the right to appoint bishops, collect tithes, approve documents, and interfere in almost every area of church life.

One of the first official representatives of the Portuguese government to visit Brazil was Martim Afonso de Souza, in 1530. Three years later, the system of hereditary captaincies was implemented, but it was not successful. In view of this, Portugal began to appoint general governors, the first of whom was Tomé de Sousa, who arrived in 1549 and built Salvador in Bahia, the first capital of the colony.

With Tomé de Sousa came the first members of a new Catholic religious order that had recently been officialized (1540) – the Society of Jesus or the Jesuits. Manoel da Nobrega, José de Anchieta, and his companions were the first missionaries and educators of colonial Brazil. This order would operate uninterruptedly in Brazil for 210 years (1549-1759), exerting enormous influence on its religious and cultural history. Many Jesuits were defenders of the Indians, such as the famous priest Antonio Vieira (1608-97). At the same time, they became the largest landowners and slave masters of colonial Brazil.

In 1759 the Society of Jesus was expelled from all Portuguese territories by the prime minister of King Joseph I, Sebastião José de Carvalho, and Melo, the Marquis of Pombal (1751-1777). Because of their wealth and influence, the Jesuits had many enemies among ecclesiastical leaders, landowners, and civil authorities. His expulsion resulted both from the anti-clericalism that spread throughout Europe and from the “regalism” of Pombal, that is, the notion that all the institutions of society, especially the church, were to be entirely subservient to the king. Pombal also determined the transfer of the colonial capital from Salvador to Rio de Janeiro.

From the beginning of colonization, the Portuguese crown was slow in its support of the church: the first diocese was founded in 1551, the second only in 1676, and in 1750 there were only eight dioceses in the vast territory. No seminary for the secular clergy was created until 1739. However, the crown never failed to collect tithes, which became the principal colonial tribute. With the expulsion of the Jesuits, who were largely independent of civil authorities, the church became even weaker.

During the colonial period, the activity of the Bandeirantes, adventurers who went through the interior in search of precious stones and slaves, was decisive for the territorial expansion of Brazil. His actions were facilitated and encouraged by the Iberian Union, that is, the control of Portugal by Spain for sixty years (1580-1640). The Bandeirantes even attacked the Jesuit missions of the Paraná river basin, known as “reductions”, bringing hundreds of Indians to the slave markets of São Paulo. The enslavement of Indians and blacks was constant in the colonial period. Another striking phenomenon was the gold rush in Minas Gerais (1693-1760), which brought benefits and problems.

In the colonial period, there were two quite distinct types of Catholicism in Brazil. In the first place, there was the religiosity of settlers, slaves, and planters, centered in the “Big House” and characterized by informality, a small emphasis on dogmas, devotion to the saints and Mary, and moral permissiveness. At the same time, in the urban centers, there was the Catholicism of religious orders, more disciplined and aligned with Rome. There were also the brotherhoods, which sometimes had considerable independence from the hierarchy.

In conclusion, in the colonial period, the state exercised strict control over the ecclesiastical area. As a result, the church found it difficult to adequately carry out its evangelistic and pastoral work. Popular Catholicism was culturally strong but weak on the spiritual and ethical levels. Despite its weaknesses, the church was an important factor in building unity and national identity.

(…)

Pentecostal and Neo-Pentecostal Churches

The three waves or phases of Brazilian Pentecostalism were as follows: (a) 1910-1940 decades: simultaneous arrival of the Christian Congregation in Brazil and Assembly of God, who dominated the Pentecostal field for 40 years; (B) decades of 1950-1960: fragmentation of Pentecostalism with the emergence of new groups – Foursquare Gospel, Brazil For Christ, God is Love and many others (São Paulo context); (C) the 70s and 80s: the advent of neo pentecostalism – Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, International Church of the Grace of God and others (Carioca context).

(A) Christian Congregation in Brazil: founded by the Italian Luigi Francescon (1866-1964). Based in Chicago, he was a member of the Italian Presbyterian Church and joined Pentecostalism in 1907. In 1910 (March-September) he visited Brazil and started the first churches in Santo Antonio da Platina (PR) and São Paulo, among Italian immigrants. He came 11 times to Brazil until 1948. In 1940, the movement had 305 “Houses of Prayer” and ten years later 815.

(B) Assembly of God: had as founders the Swedes Daniel Berg (1885-1963) and Gunnar Vingren (1879-1933). Baptists of origin, they embraced Pentecostalism in 1909. They met at a Pentecostal conference in Chicago. Like Luigi Francescon, Berg was influenced by Baptist pastor William H. Durham, who participated in the Los Angeles revival (1906). Feeling called to work in Brazil, they arrived in Bethlehem in November 1910. Their early adherents were members of a Baptist church with which they collaborated.

(B) Foursquare Church: founded in the United States by evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson (1890-1944). Missionary Harold Williams founded the first IEQ in Brazil in November 1951, in São João da Boa Vista. In 1953 began the National Crusade of Evangelization, Raymond Boatright was the main evangelist. The church emphasizes four aspects of Christ’s ministry: He who saves, baptizes with the Holy Spirit, heals, and will come again. Women can exercise pastoral ministry.

(C) Evangelical Pentecostal Church Brazil For Christ: founded by Manoel de Mello, an evangelist of the Assembly of God who later became pastor of IEQ. Separated from the National Crusade of Evangelization in 1956, organizing the campaign “Brazil for Christ”, from which the church arose. He joined the WCC in 1969 (he resigned in 1986). In 1979 he inaugurated his great temple in Sao Paulo, being official speaker by Philip Potter, secretary-general of the WCC. Present was the Cardinal Archbishop of São Paulo, Paulo Evaristo Arns. Manoel de Mello died in 1990.

(D) Church Deus é Amor (God is Love): founded by David Miranda (born in 1936), the son of a farmer from Paraná. Coming to São Paulo, he became a small Pentecostal church and in 1962 founded his church in Vila Maria. Soon it was transferred to the center of the city (Praça João Mendes). In 1979, the “world headquarters” was acquired in Baixada do Glicério, the largest evangelical temple in Brazil, with a capacity of ten thousand people. In 1991 the church claimed to have 5,458 temples, 15,755 workers, and 581 hours per day on radios, as well as to be present in 17 countries (mainly Paraguay, Uruguay, and Argentina).

(E) Universal Church of the Kingdom of God: founded by Edir Macedo (born 1944), the son of a merchant from Rio de Janeiro. He worked for 16 years in the State Lottery, during which time he went up to an administrative post. Of catholic origin, it entered the Church of New Life in adolescence. He left this church to found his own, originally called the Church of the Blessing. In 1977 he left public employment to devote himself to religious work. That same year came the name of IURD and the first radio program. Macedo lived in the United States from 1986 to 1989. When he returned to Brazil, he transferred the church’s headquarters to São Paulo and acquired Rede Record de Televisão. In 1990 the IURD elected three federal deputies. Macedo was imprisoned for twelve days in 1992, under the accusation of stelionate, quackery, and healers.

(Summary)

BREVE HISTÓRIA DO PROTESTANTISMO NO BRASIL

Anti-Protestantism as a symptom.

Brazil was colonized under the sign of the Counter-Reformation.

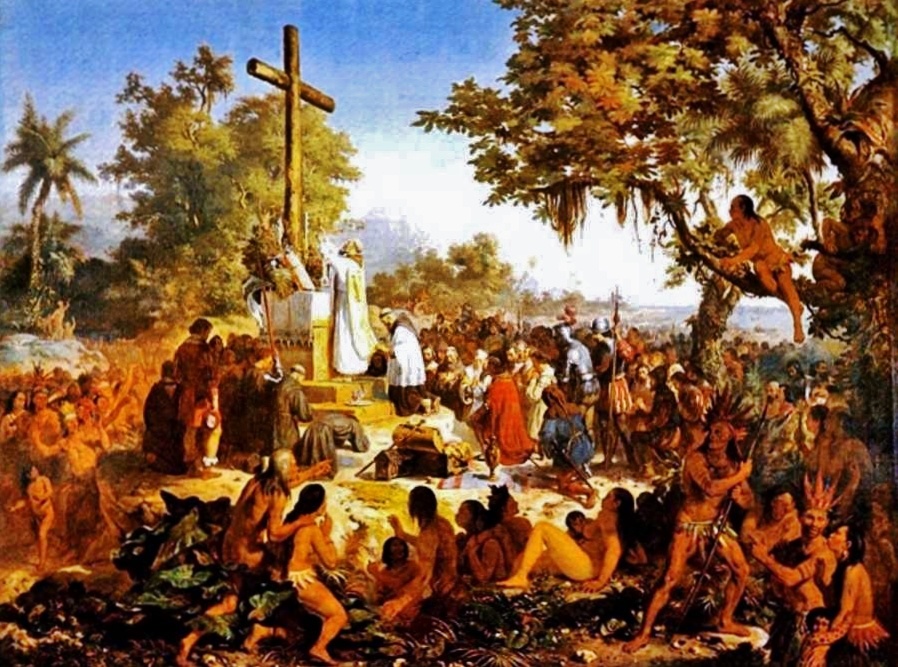

First Mass in Brazil. Victor Meirelles’ work.

Watercolor. unknown author (featured image)

See too:

Reformers – João Ferreira de Almeida (1628 – 1691)

LikeLike

Thanks for your work here. It’s the best quick overview of Brazilian church history I’ve come across. I knew Raymond Boatright very well, and have friends who were there when the Revival of Brazil launched in SP in 1953 (in a Presbyterian church.) I also knew Robert McAlister and Cecilio Fernandes, each of whom influenced Macedo (and therefore had keen insight into him and his movement.) There is a lot of Brazilian church history yet to be written. You give me hope that one day it will be. Obrigadão. William

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, it is a beautiful text by Alderi Souza de Matosa, and a brief compilation of the story.

The commentary contains some more information about the current Brazilian reality.

Thanks for reading and commenting, William!

LikeLike

But this is a people robbed and spoiled; they are all of them snared in holes, and they are hid in prison houses: they are for a prey, and none delivereth; for a spoil, and none saith, Restore.

Who among you will give ear to this? who will hearken and hear for the time to come?

Who gave Jacob for a spoil, and Israel to the robbers? did not the LORD , he against whom we have sinned? for they would not walk in his ways, neither were they obedient unto his law.

Therefore he hath poured upon him the fury of his anger, and the strength of battle: and it hath set him on fire round about, yet he knew not; and it burned him, yet he laid it not to heart.

Isaiah 42:22-25

LikeLiked by 1 person

LikeLiked by 1 person